Novel text

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5

-

6

-

7

-

8

-

9

-

10

-

11

-

12

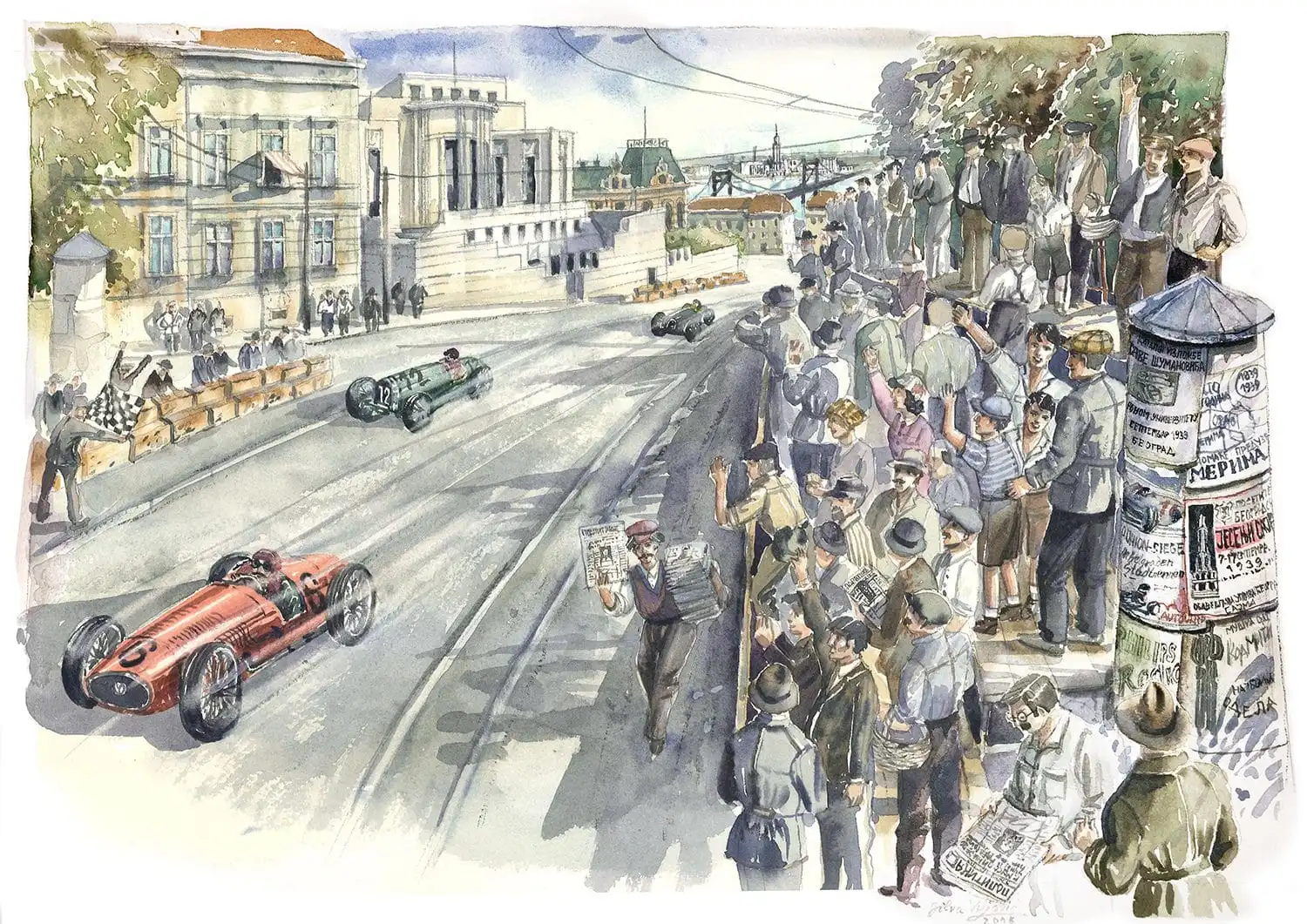

A Day at the Races

It was such a beautiful day in Belgrade. Aleksandar was excited-– today was the day Belgrade hosted the Grand Prix at the circuit around Kalemegdan Park! The park engulfed the centuries old fortress, nestled on the hill that overlooked the place where the Sava and Danube Rivers met, guarding Belgrade. Already for weeks he was talking about this race with Bogdan, his best friend and classmate. Aleksandar’s father kept his promise to take the boys to the races. They arrived very early in the morning to the stands opposite of the French Embassy. Prepared to spend a whole day at the races, they brought along a basket of food. Tens of thousands of Belgraders took to the green fields of Kalemegdan park, where people’s excitement collided with the shouts of peddlers selling sunflower seeds, hot pereci (pretzels), bagels, boza, klaker and kabeza (sugared soda).

Cousin Pavle was also at the race with them. Aleksandar was very fond of him. Pavle was about ten years older and Aleksandar looked up to him. Secretly, Aleksandar would try to part his hair so that there was a lock hanging a little over his forehead, the same way Pavle did. Since Aleksandar’s mother always combed his hair back meticulously, in order for him to look neat and tidy, Aleksandar thought of Pavle’ s stray lock as very significant proof of maturity and independence. When I grow up, I will wear my hair the way I want! he thought to himself.

But that day was all about the races. Aleksandar and Bogdan had already investigated everything they could find about the race cars and the drivers of the Belgrade Grand Prix.

“There are no less than four world champions in Belgrade right now!” Bogdan kept repeating excitedly.

People were talking about famous race car drivers like the Yugoslavs Boško Milenković and Pavle Melamed, matching against Nuvolari–the flying Italian, and German champions Manfred von Brauchitsch, Lang and Müller. Disappointment over news that French and British stars such as Jean-Pierre Wimille, René Le Bègue, and Cuth Harrison canceled their participation permeated through the crowd. The newspaper salesmen shouted in the distance “Fighting in Poland, Mr. Mussolini proposes an end to hostilities and an emergency conference for England, France, Germany, Italy and Poland”.

The boys had a long discussion about which race car was the best–the Bugatti or Mercedes? Eventually they asked Pavle, whose opinion was most appreciated and revered by the boys. The technicians and mechanics ran nervously around the shiny cars that were ready to start their engines.

“Mercedes because it is a German car.” Pavle said. But he didn’t have time to explain why because his voice was drowned out by the noise of the crowd-– the race was on.

When a beautiful red Mercedes Benz dashed out of a curve, they both agreed that it was by far the best car in the world.

“Mercedes Benz W-154 M163” Bogdan could barely utter the words.

“Father, can I move closer to take a better look at the Mercedes?” asked Aleksandar.

Engulfed in a pungent smell of gasoline and scorched tires, the shouting of the excited crowd and through the noise of engines and squeaky wheels–his father’s voice assured Aleksandar that they would definitely visit the car show to see the new Mercedes models at the Belgrade Fair later in April.

When the races were over and the crowd had long dispersed, Aleksandar and Bogdan stayed. They were somewhat solemnly aware that they would remember that day for the rest of their lives. They lingered for a long time, staring at the golden September sky, looking beyond the Sava river. Their gazes reached even further, where only children’s eyes could reach.

Visiting the Car Exhibition

s they approached the main gate of the Belgrade Fair, Aleksandar was thinking about the way his mother had wrapped him up firmly with a thick scarf. She said that one could never trust Baba Marta 1, еven in April, while they were leaving the flat. He asked his father who Baba Marta was but his father just laughed heartily and brushed it off.

“Come on, forget about Baba Marta or apples and oranges now, look at this! This is the future, this is the gate to Europe for our Belgrade.” he said, pointing to the main gate of the Belgrade Fair.

“One day you and your children will live in a much better world, in a world in which men will use industry, science and technology to make everybody’s lives better! And here, at this very spot, Belgrade becomes a part of that future. I am lucky to be living in these times and to have seen this, and you, my son, are even luckier for this is how your future will be.” Father spoke deeply inspired. “Europe, my son, this is Europe!” he shook his head and sighed deeply as he walked along.

The whole city was decorated in splendid lights, the most important buildings were lit with spotlights and King Aleksandar’s bridge particularly shone, glistening in special lights that led towards the fair. As they were entering the fair, Aleksandar was impressed by father’s enthusiasm and looked solemnly and proudly at the flags of various countries that were fluttering above each pavilion.

“Father, can we first…?” he uttered and paused but the father already knew what he had in mind.

“Yeah, yeah, we shall go straight to the Car Exhibition!” Father exclaimed.

That day, the Car Exhibition Pavilion was the most exciting place in the world! There were so many people around and Aleksandar’s view was blocked by their wide winter coats. He could clearly distinguish the specific smells of engine oil and petroleum. Brand new car models from various world manufacturers were arranged in several rows along the width of the pavilion. Visitors were separated from the cars by only a rope that stretched between posts, marking the edge of the exhibition space. Aleksandar finally managed to get through the crowd and find the brand new Mercedes Benz model. He wanted to stretch out his arm over the rope and feel the metal frame of the car, at least with just the tip of his finger but he did not dare. It was in the Car Gallery that his father met Mr. Demajo.

“Good afternoon, Mr. Frelih!” Mr. Demajo greeted father cordially with a strong voice, offering his hand to him.

“How was your lecture about Zionism at the Jevrejskoj čitaonici? I’m sorry I couldn’t make it but I followed your discussions in the newspapers with great interest” Father answered.

Aleksandar quickly concluded that Mr. Demajo was a very important person, for it seemed that he was greeted by everybody who was passing by. Since his father and Mr. Demajo kept chatting, Aleksandar lost his patience and couldn’t wait any longer–he turned back to the new Mercedes Benz. He remembered Pavle stating that German cars were the best and he studied it very thoroughly, paying special attention. He could see his own reflection in the shine of the polished round metal as well as the reflections of the people passing behind him. He could already feel his excitement growing, knowing that the next day at school he would tell Bogdan about everything. In fact, he was a bit sorry that Bogdan was not there, then they would be able to look at various car models and analyze them together, though probably they would end up quarreling about which model was the best. Aleksandar smiled at this thought. We are not fighting for real, he thought, as if he was trying to excuse himself.

Bar Mitzvah

“His Majesty Aleksandar I, King of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, a member of the national dynasty of the Karadjordjević’s, on the 15th of June 1924 and on the 13th of Sivan 5684, Aleksandar I laid the foundations and placed the first stone to build the first building that would house the Ashkenazi Serbian-Jewish religious community in Belgrade” Aleksandar read.

“That’s right” said uncle Julije. “And then this charter was signed by King Aleksandar and Queen Marija and laid into the foundations of the sinagogue!”

“The king and the queen laid the charter into the foundations? With a shovel?” Aleksandar opened his eyes wide.

“Not at all!” Uncle Julije laughed, “The shoveling was done by the workers, while the King and the Queen signed the charter and thus blessed the construction of the Ashkenazi synagogue in Belgrade and the school, offices, mikvahs, gym and apartments for the employees of the Serbian-Jewish religious community.”

“And that is why you live in an apartment in the synagogue, you are an employee, aren’t you?” Aleksandar responded.

“That’s right, a Gabbai, or as some used to say a Shamash. I work in the synagogue and we live in the apartment over there.” Uncle Julije answered patiently.

“Does this make Pavle an employee too? He also lives in the synagogue, doesn’t he?” Aleksandar kept asking.

“Not at all!” Julije laughed, “Pavle lives in the synagogue because he is my son. Your aunt also lives there because she is my wife. It is quite natural for a family to live together in an apartment. You live with your father, mother and Selma too, don’t you?” his uncle spread his arms explaining.

“Well, yes,” answered Aleksandar as he was absorbing this information. “But will Pavle be a Gabbai too one day?”

“I doubt it. He is not very keen on it.” Uncle Julije shook his head. “He is more into earthly matters. You yourself know that he is assisting Mika Altaras at his shop, saving money for a college education abroad. He wants to go to Prague. That’s where our cousin Solomon studied too. But, it’s not possible to go there anymore, so he’s thinking about trying to study in Switzerland.” answered Julije.

“Earthly matters…?” repeated Aleksandar, “You mean, like planting potatoes?” Aleksandar was trying to understand.

– Ma ne – opet se smejao stric Julije – Pavla zanimaju nauke, kao matematika ili mehanika, ovozemaljska znanja, a ja sam uvek bio više za duhovne nauke, da učim Toru i razumem svet kroz Božije učenje.

“So, you are like a Rabbi, aren't you?” the boy kept asking.

“Well, I am not a Rabbi. Ignjat Šlang is a Rabbi” Uncle Julije gestured with his head towards the Rabbi standing across the courtyard, “But I assist him in everything which concerns services and the synagogue itself. All practical matters, whatever is necessary. That is what a Gabbai does.” Julije said proudly.

Aleksandar was watching Rabbi Šlang, who was at the top of the stairs in front of the right entrance to the building. The women were finely dressed in their best sophisticated skirts and their best shoes, while the men donned smart suits and felt hats. Aleksandar’s sister Selma felt so pretty in her red dress, which fell to her ankles, so she could twirl around exposing her small, shiny black shoes. Their parents, Rihard and Ranka, held each other by the waist lovingly. The Rabbi was walking from one group of guests to another, talking to everybody for a few minutes. Being solemnly dressed in his attire, with his big silver beard, to Aleksandar he looked like a sage from the old stories about Moses and Joshua. The wide, stone paved courtyard was glittering with the colourful reflections of the intricate stained glass windows of the synagogue that was bathed in the May sun. The illuminated shadows danced in spirals on the ground.

Today was a joyous day. Moša and Jakov turned thirteen and were having their Bar Mitzvah together. Aleksandar remembered when his father explained to him what a Bar Mitzvah was. “Young persons acquire their rights, as well as their responsibilities as adults, thus becoming accountable for their decisions and actions.” Moša and Jakov had their pictures taken in front of the wall, close to the gate, with white tallits around their necks. They were a little nervous but proud and happy. How could they possibly not be happy? thought Aleksandar, impatiently daydreaming about the day when he would have his own Bar Mitzvah. He was not quite sure what exactly would change in his life after that but since he would be considered an adult, he was hoping that he would be able to wear his hair the way Pavle did. That seemed a rather good start to adult life! His eyes searched for Pavle across the courtyard. There he was! Pavle was standing with his mother, Aleksandar’s aunt. With a deep sigh of resignation, Aleksandar concluded that Pavle’s dark silk kippah was so sophisticated and elegant, while his own white knitted one was so childlike.

Uncle Julije descended the stairs to the courtyard followed by Aleksandar, who came skipping down to the guests. The parents of Moša and Jakov, proud and smiling, were just receiving congratulatory remarks from Aleksandar’s father and mother.

“Mazal tov, mazal tov!”

“Thank you Rihard, thank you Ranka!” replied Mr. Leon, Moša’s father, grabbing and shaking first Aleksandar’s father’s, then mother’s hand, with a huge smile on his face. “Wow, Selma has grown so much!” Mrs. Simha, Moša’s mother, squatted before Selma, holding her gently by the shoulders, looking straight into her eyes, nodding her head as if amazed in disbelief. Selma just smiled and blinked her eyes.

“Come, Aleksandar, you should congratulate them too.” Father added. Aleksandar checked with his fingertips if his kippah was adjusted well on his head. He remembered how once Bogdan’s mother had admonished Bogdan for his school cap being askew, “You shouldn’t behave as if you were a circus clown”.

“Mazal tov!” Aleksandar was shaking everyone’s hands one after another.

How strange it is that Moša is our relative and Jakov isn’t, while on the other hand, Moša and Jakov are related to each other. These family relationships are so complicated! thought Aleksandar, And yet again, it doesn’t really matter too much-– take Bogdan for example, Bogdan is not related to me, and yet I feel like he is almost closest to me. Only my mother, father and Selma are closer because we are family. And Pavle, of course.

Passers-by kept coming down Kosmajska Street, walking slowly, and enjoying the Sunday sun. Some of them would stop for a while, smiling at Moša and Jakov, some would even wave “Mazal tov”, while others would mind their own business or be too absorbed in their thoughts. They probably didn’t even notice the celebration in the synagogue’s courtyard.

Hanging around among the guests, in the sounds of laughter and joy, Aleksandar noticed that the voices started to sound different in one spot. They were muffled and worried. A war was being mentioned. “A war is a terrible evil that brings out an animal in a man.” Aleksandar recognized the voice of uncle Julije. He stealthily moved closer to hear better.

“It will bypass Yugoslavia, as long as we don’t take sides…” a female voice uttered. Some other male voice responded. “But have you seen what is happening in Poland now and what happened in Germany a few years ago?” Then he lowered his voice, “Kristallnacht…that was terrible, pogroms again. And then Anschluß Österreichs! Outrageous!”.

“It is said that those things had nothing to do with the Jews. They were against communists. It was communists they were after, not us. That’s what I heard”.

“I think Hitler won’t last for long. Mark my words!” Replied another voice. “Germans are a civilized nation, gentlemen. They are not like us. For them, order is the most important thing. That and honest hard work!”.

“I still worry, though. Can’t you see that the refugees are coming from Vienna? From Vi-e-e-en-na, gentlemen!” A voice whispered in a hoarse tone, distorting the “e” vowel. Vienna must be some very special place, thought Aleksandar.

“What refugees?” A female voice interjected worriedly.

“The Vienna Jews, my darling,” continued another female voice, “They are fleeing towards Palestine. One of them was at the Demajos’ for Shabbat. They say it was terrible when Hitler’s supporters showed up. Terrible!”

“Don’t be naïve! It can also happen to us. You’ll see! Our authorities are afraid of Hitler too. They already dance to Hitler’s tune!”

“But…what does Hitler play?” Slipped out of Aleksandar’s mouth. Having heard that, everyone straightened up, surprised. They all fell silent and then burst into laughter.

“Go there and play with other children!” Uncle Julije gently patted him on his head and softly pushed him towards Moša and Jakov.

But Moša and Jakov were not kids anymore, thought Aleksandar.

Hanukkah 1940

“I think…” Selma talked, licking the chestnut puree off her spoon with pleasure “Hanuka is really great!”.

“I also think Hanukkah is great,” said Aleksandar getting annoyed, “But Bogdan cleans his boots well and leaves them in front of the door for Saint Nicholas and the next day there is a present for him in the boot, if he was a good boy.”

“Well, all right, that is also nice,” his mother said, preparing another spoon of chestnut puree for Selma. Forming a round mouthful big enough and small enough for her little mouth. “And a lot of Serbs celebrate Saint Nicholas day as slava 1. So does Aunt Zora…Do you remember Aunt Zora Hercog? As a matter of fact, her married name is Branković now,” Aleksandar’s mother looked at her children inquisitively for a while and then continued, “Aunt Zora is married to a Serb, so she celebrates Saint Nicholas day too. Yet, she also pays visits to her father’s family for Hanukkah!”

“And she gets her Hanukkah gelt twice!” Selma concluded, excited.

“A Saint Nicholas present is not called Hanukkah gelt!” Aleksandar corrected her.

“What is it called then?” asked Selma.

“I don’t know…a present, I suppose?” Aleksandar mused, taking a big spoonful of chestnut puree.

They were sitting at a table on Terazije Street in front of the confectioner’s, just next to Hotel Moscow and a shop called Tivar. Tivar sold suits and ready-made clothing but they also had a toy department. After ordering two portions of chestnut puree for Selma and Aleksandar several minutes ago, their father “remembered” that he had something to do and went into the shop. Aleksandar knew very well that his father had actually gone to buy some presents for them for Hanukkah but it was all a part of the exciting game. He never minded pretending that he didn’t know what it was all about.

A lazy and calm winter evening descended upon Belgrade. The green spires of Hotel Moscow, which housed the whispers of intellectuals and writers that would prophesize there, overlooked the buzz of the crowd outside passing by and sitting under neon signs. The noise of conversations and the steps of passers-by echoed across the wet pavement as trams on line 1, riding from Kalemegdan to Slavija, squeaked along the tracks. They would ring sharply ding, ding, ding, cutting the air and warning the pedestrians that always lingered in the same spot that they were crossing the street.

Aleksandar liked Hanukkah days, not only because of the presents but he also enjoyed the mysterious little flames of the candles they would light every evening-–one more each evening-–on their eight-branched candle holder, hanukkiah. In fact, a hanukkiah had nine branches but the candle in the very middle of it didn’t count, for it was merely used to light all other eight candles. During these days they were visited by uncle Julije, the aunt, Pavle and other relatives. The adults would play cards, while children would spin a dreidel, singing “nes gadol, haja šam”. Although Pavle was no longer a child, he would still sit with the children spinning a dreidel. He was the best at it. Later uncle Julije and Aleksandar’s father would speak about brave Judah Maccabee, whose name means hammer in Hebrew. In ancient times, when terrible occupiers had forbidden Jews to be Jews, Judah fought. He fought for three years and liberated Jerusalem and the whole Jewish nation. Aleksandar was moulding his chestnut puree into a hill in the glass dish, building the Temple at the top and picturing Judah Maccabee swinging his hammer bravely charging uphill to liberate the nation.

“Aleksandar, for god’s sake, don’t play with your food!”

“Sorry, mother,” Aleksandar awakened and put a huge bite of chestnut puree into his mouth.

At that moment, father came back.

“Well, I have done all that I had to. Have you finished?”

“We had such a nice chestnut puree,” Selma explained to father as they headed home down the pavement.

Ding, ding, ding, a tram greeted them.

***

Several days later, the children received their presents. Selma nicknamed her plush teddy bear Pepi, from that point on they became inseparable. Aleksandar got a beautiful red toy race car. It may not have been exactly the same model but to him it looked just like the Mercedes Benz W-154 M163, the winning car at the great Belgrade Grand Prix around Kalemegdan Park.

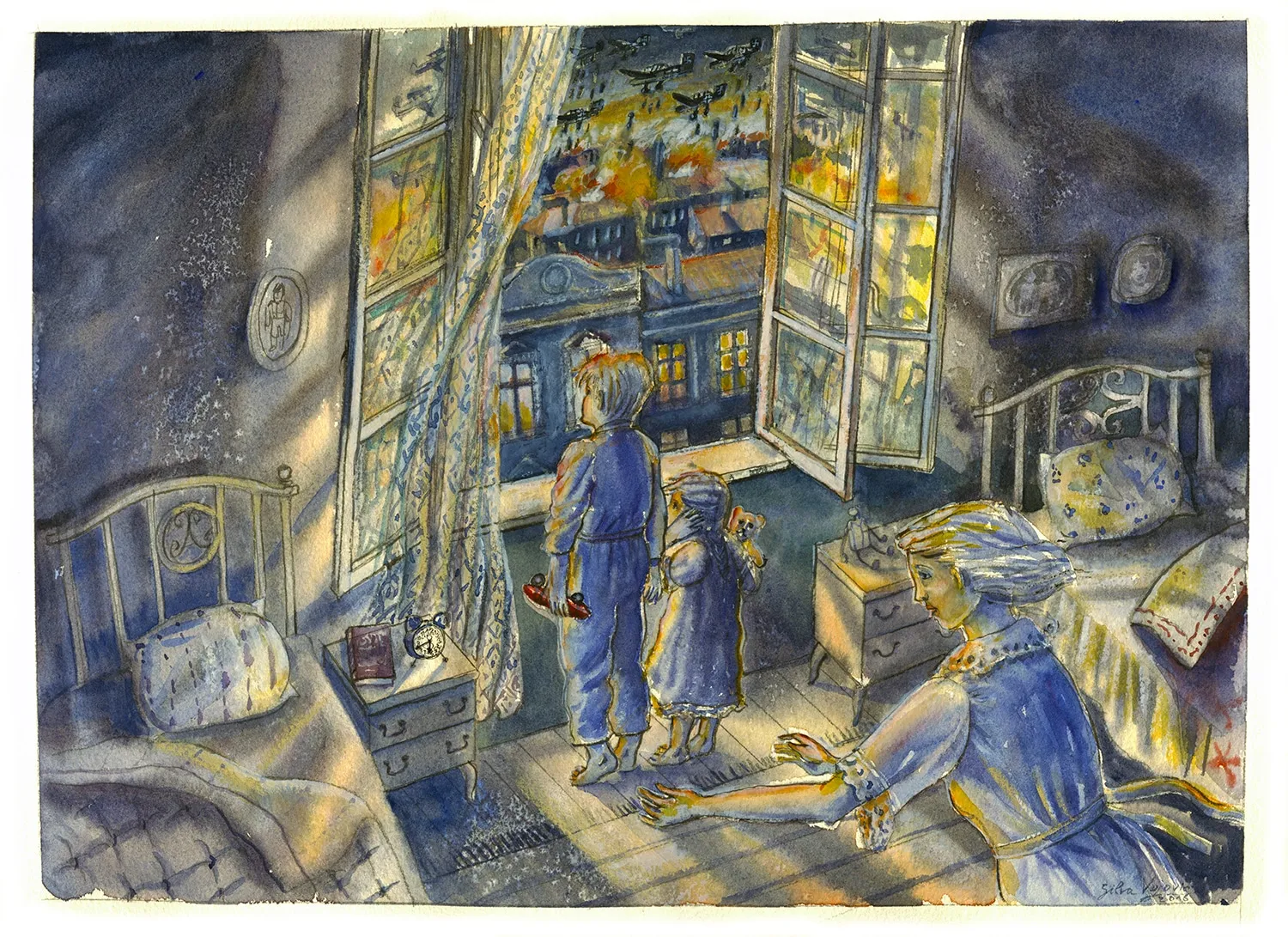

Bombing of Belgrade

Aleksandar was lying on his stomach reading the Politikin Zabavnik 1 out loud to his whole family. Reading Poltikin Zabavnik together was one of the favourite pastimes on Saturday evenings after the end of Shabbat.

“Brick Bradford,” Aleksandar was reading the title of a comic with an exaggerated theatrical voice, “An Indian Doll with Diamond Eyes, chapter twenty-six, Brick Saves the Professor!” As he read, he made grimaces with his eyes wide open, imitating the Indian doll. Selma was lying on the floor next to Aleksandar, repeating everything to Pepi.

“Brick Bradford! An Indian doll with dianmond eyes!”

“Diamond!” Aleksandar corrected her.

“Dian…diamond eyes!” Selma corrected herself, nodding her head significantly at Pepi so that it could also understand.

“As Brick was descending the well, the professor disappeared under the surface of the water…” Aleksandar pronounced the words dramatically making gestures with his hands as if he were swimming.

“…under the water surface!” Selma shook Pepi as if trying to persuade the toy about what great danger awaited the professor.

Their mother and father were sitting aside laughing out loud at this show.

Every evening before going to bed, Aleksandar and Selma would come to father, who would be sitting at the big dining table made of oak wood. They would kiss him, wishing him goodnight. The father would pat their hair and kiss them, then the mother would take them to their room. It would be dark in their room but light would come in from the dining room making an elongated pattern along the carpet. Mother would check if the window was closed, straighten the curtain a little and then cover Aleksandar with his blanket, kissing his forehead saying “My golden boy”. Then she would sit on Selma’s bed for a while, kiss her and say “My sweetest heart”, closing the door behind her as she would leave the room. The elongated pattern of light on the carpet would abruptly disappear as soon as the door would close, while the dim, pale street light would sneak into the room, casting shadows on the part of the wall above Aleksandar’s bed. Sometimes, when it was windy, a tall oak tree growing in front of the building would rustle. Flickering shadows of leaves playing on the wall.

Aleksandar quietly pulled out his red race car from under the pillow. In the semi darkness of the room it looked mysterious, as if magical. He passed his fingers over the smooth surface of the car and then spun the wheels with a carefully measured move of his index finger. He would spin them and then listen to them rustling until they would slow down and eventually stop. Then he would spin them again.

All of a sudden he found himself at the steering wheel, convulsively shifting gears and squeezing the wheel. Lo! There was Bogdan too, sitting next to him beside the driver’s seat in the red Mercedes Benz W-154 M163, the invincible race car of world champions. Aleksandar and Bogdan were racing around Kalemegdan Park. Engulfed in a pungent smell of gasoline and scorched tires, the shouting of the excited crowd and through the noise of engines and squeaky wheels, they passed the stands where father and Pavle were watching. What a surprise it would be for father and Pavle to see the two of them! Aleksandar kept shifting gears and the engine was roaring very loudly, more and more all the time. Aleksandar turned around, something was wrong, he let go of the wheel. The engine was droning very loudly. Bogdan hid his face in his hands. Something was wrong! Cars kept racing passed them, everywhere, hundreds of cars, hundreds of engines. Aleksandar grabbed his head in both hands.

“Aleksandar!” he heard Selma’s voice. She was standing beside him with Pepi in her hand. Aleksandar sat up on his bed. He was not sure if he was still dreaming or not. All these engines, where was the sound coming from? They slowly moved to the window. Something could be heard. He slowly opened the window pushing aside the curtain. The noise of the engines rattled louder and louder. Airplanes swarmed in the sky, like dense flocks of black birds with their wings spread wide. The whole skyline was covered with their silhouettes. Selma shielded her ears with her hands. Then they heard the sirens.

“Aleksandar?” Selma whined in fear.

The first bomb exploded in a fireball with a loud bang as they felt the whole building shake, stepping back into the room with their eyes wide open. Their mother was already there behind them, grabbing their hands and pulling them inside.

“Quick, let’s go to the shelter!”

“Mother, what is this?”

“Germans. The war has started.”

Aleksandar seemed to hear the voice of his uncle Julije, a war is a terrible evil bringing out an animal in a man.

Occupation

After the German bombers of the Fourth Air Fleet under the command of general Alexander Löhr had dropped 440 tons of their deadly cargo above the city, Belgrade had been covered with a cloud of sand and dust for days. Ruins, demolished walls, cracked facades and glass emerged through the cloud. Beams, roof tiles, newspapers, flowerpots and bricks lay in the streets. A dull sound of the last explosion seemed to still moan across the streets, while all the words and letters of 350,000 books of the National Library of Serbia were still falling over the city–mixing with the ashes and the wails of the wounded, who lay buried under the rubble of Vaznesenjska Church. The roars of the polar bears, lions, deer and the screams of royal cranes dying in the ruins of the Belgrade Zoo, could be heard below Kalemegdan Terrace restaurant. Everything was carried by the whirlwind all the way to Dobračina 18, where Aleksandar was standing at the window, silently watching his street through the cracked glass.

***

The first German units had entered Belgrade on the 12th of April. German soldiers and Volksdeutsche volunteers from Zemun and Belgrade started looting the property of Belgrade citizens, especially Jewish shops and apartments.

In the following days, military occupation administration was established, comprised of an extended repressive apparatus where the Operative Police Group and the Operative Police Headquarters headed by SS-colonel Wilhelm Fuchs and SS-major Karl Kraus, respectively, played major roles. The Operative Police’s centre was the notorious sub department IV of the German Security Police-–Gestapo, within which the Police Department for Jewish Affairs, the Judenreferat, was established immediately under the command of SS-colonel Fritz Strake.

Aleksandar was not aware of all of it. However, when his mother and father had read the announcement issued by the chief of the Operative Police Group on the 16th of April, he heard that under death threat, Jews were ordered to sign up at the Special Police Headquarters at Tašmajdan park on the 19th of April. Thereby, a process of registering and identifying Jews by yellow armbands had started.

Aleksandar’s father was already discharged from public service on the 20th of April. Instead of going to work, he had to go do forced labour together with other Jews. In the wake of the aftermath of the bombing, they had to clear debris from city streets and pull out the dead from under the ruins. Later on, on the quay of the River Sava or at the rail station they loaded arms and equipment confiscated from the Yugoslav army, food supplies from looted food warehouses, equipment from looted factories and looted merchandise from Jewish and Serbian shops. Besides that, Jews were forced to do other hard labour jobs that were meant to humiliate them as much as possible, Jewish women not being excluded and spared.

One by one anti-Jewish decrees came. Published in newspapers or on placards plastered all over the city streets: All Jews are allowed to buy goods at markets or in shops only after 10.30 a.m! Jews are allowed to supply themselves with water at public fountains only when all other citizens satisfy their needs first! All retailers are forbidden to sell goods on the black market to Jews under a threat of fines, imprisonment or being sent to a concentration camp! Jews are not allowed to possess cameras! Jews are not allowed to possess refrigerators! Jews are not allowed to use telephones! Jews are not allowed to possess radio receivers! Jews are not allowed to ride on trams!

Eventually on the 31st of May, all of these decrees, which had been announced by the German military occupation administration sporadically, were officially published and codified in The Official Gazette of the Decrees by the Military Command in Serbia under the title “Orders Referring to Jews and Gypsies”. Special commissioners were appointed to “manage” Jewish enterprises and shops.

At the end of April the Council of Commissioners was established, governed by Milan Aćimović who also headed the Ministry of Internal Affairs. By his order, the Belgrade City Administration was formed and headed by Dragi Jovanović, representing the highest Serbian administrative and police authority in Belgrade. Its most important police agency was the Department of Special Police within which sub department VII for Jewish and Gypsy Affairs, was headed by Jovan Nikolić, who was in charge of the implementation of all measures against Jews and Gypsies. Apart from that, a Gendarmerie Command was formed consisting of about 3,000 Serbian gendarmes.

“Traitors,” the father commented with disgust, while mother helped him take off his dusty coat after a whole day of forced labour. “Oooh, easy,” with a painful grimace he bent down slowly, pulling his arm out of the sleeve. Then he collapsed on the chair at the dining table made of oak wood, bowing his head and breathing deeply. The whole dining room filled with the smell of sweat and dust, “They are all nothing but traitors, scum and German servants!”

Since May, and in June particularly, masses of Serbian refugees started coming to Belgrade from other parts of Yugoslavia, mainly from the Ustasha’s Independent State of Croatia, bringing news of terrible persecutions and slaughters.

During summer, protests appeared on Belgrade walls: Down with the Occupiers!, Death to Fascism, Freedom for the People!, Long live the People’s Fight!, Serbia cannot be Pacified!, Long live Brotherhood with Russia! There were rumours about a resistance movement. News started coming out about ambushes; German press burned, telephone cables cut, railway tracks sabotaged, a German military garage set on fire and attacks on police officers and German soldiers. The occupiers suffered their first casualties.

The newspapers kept writing that “These were all crimes committed by communists and Jews”. Soon the mass reprisal shootings by firing squads followed. SS-General Harald Turner, chief of Serbian Military Administration, issued an order to regional and district military commands all over Serbia under German occupation to take primarily Jews as hostages for mass reprisal shootings.

A few months later, Germans would officially issue the order that 100 hostages should be executed for every German soldier killed and 50 for every wounded.

After the attack of Nazi Germany on the USSR on the 22nd of June, 1941, there was a wave of mass arrests of communists and their supporters. Consequently, a concentration camp was built in Belgrade at Banjica for the arrested. Other enemies of the occupiers and the puppet regime were imprisoned there too. By the middle of September, Jewish men were also brought to the camp. The inmates at Banjica were the main source of hostages for mass executions.

The newspapers kept publishing titles like “This amount of communists and that amount of Jews were shot for reprisal.” Citizens of Belgrade were being oppressed even harder. The night curfew was extended and started even earlier for Jews than for the rest of the citizens.

On Sunday, the 17th of August, Germans shot and then hung five Serbian partisans and anti-fascists on electric posts in the very center of Belgrade at Terazije Street. On that very day, Volksdeutsche in Belgrade and Zemun, organized a mass parade and marched in uniformes across Terazije Street, under the hanged bodies, making their way through the city.

At the end of August, a concentration camp for Jewish men was created in Topovske Šupe in Autokomanda, former Yugoslav military barracks in the Belgrade suburbs. The first inmates were Jews from Banat and then those from Belgrade too. In the beginning of October, the camp at Topovske Šupe was to become the main source of hostages for mass shootings. At the end of that same month, besides Jews, Germans started to imprison Roma men from Belgrade and surrounding settlements.

***

Belgrade seemed to be disfigured by pain, moaning under the Nazi jackboot, its cruel and terrible thud echoed through the city. The echo of moans was carried by the whirlwind all the way to Dobračina 18, where Aleksandar was standing at the window, silently watching his street through the cracked glass.

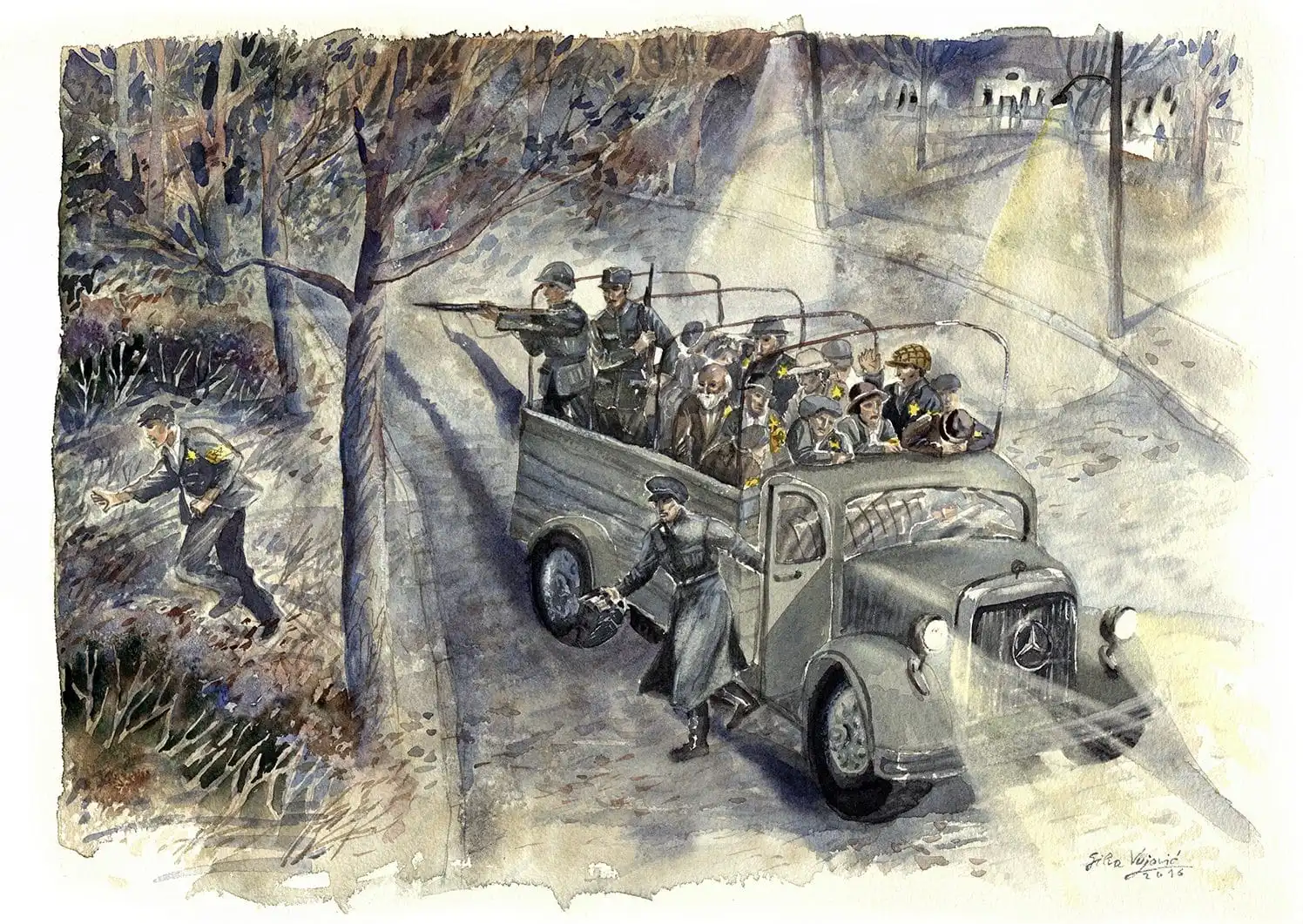

The Escape

That day, at the meeting point in the courtyard in front of the Special Police for Jewish Affairs at George Washington Street 21, where they had to report every morning, Aleksandar’s father and Pavle, together with a group of fifteen other Jews, were assigned to forced labour at the pier. Pavle’s father Julije had already been sent with the other group, but they didn’t catch where. They were loading and reloading sacks and wooden crates at the quay the whole day until dusk. Instead of being allowed to go home, they were ordered to line up in two rows and wait. They were not allowed to sit down, so some fifteen people, dirty and exhausted by a whole day’s hard work, were shifting their weight from one leg to another, whispering among themselves and guessing why they were not allowed to go home like usual.

“They are purposely holding us Shabbat!” someone said.

“Some ten days ago fifty people were shot dead by a firing squad in Belgrade as reprisal for the murder of a German soldier!” whispered someone from behind. “Good Lord!” trembled someone else’s voice.

A moustached Serbian policeman was walking anxiously around the group. Up and down, muttering, swearing and cursing. “Why during my shift? Why? Damn Yids!” Two German soldiers were standing a little further away, leaning against the wall of a building, smoking and talking. One of them laughed out loud. The sound of a dog barking was heard somewhere from the neighbouring yard.

Aleksandar’s father was standing stooped, with his shoulders lowered, slow and exhausted. Pavle tried to hold him under his arm but he just waved it off saying “Let it go!”, he adjusted his cap, sighed deeply and straightened up. Pavle was standing nearby, ready to hold him if he stumbled.

“What are we waiting for?” Pavle asked, “The evening curfew has already started!”

“Who knows?” father sighed deeply.

The easy September breeze carried the smell of the river which mixed with the smells of sweat and dust absorbed by the hairs and the suits of the tired people. An elderly man coughed heavily and moaned as he stood in the row.

“Mister p’liceman, would you be so kind as to ask the Germans to let us sit down for a while. This man is not feeling well, he is an elderly man and he cannot stand any more, please sir?” someone asked.

“You communist gang!” the policeman shouted at him with his eyes wide open, grasping the strap of his gun with a quick movement of his hand as if he was about to take it off his shoulder, “Why don’t you ask them, smart ass!?”

Then there came a truck. It stopped next to two German soldiers. The driver sat at the steering wheel without turning the engine off, while a German officer got out of the truck cabin. The two soldiers straightened up, standing at attention as the officer said something to them briskly. These two immediately ran to the group of lined up Jews and started to force them onto the truck. Pavle held Aleksandar’s father, who was not trying to let loose any more. He helped him climb up and then held and pushed a few more elderly men upward, eventually jumping on the truck himself.

“Pavle, my son, this is not good at all,” the father shook his head worriedly, “Never before have we ridden in a truck in the evening.”

“Uncle, what do you think? Where are we being taken to?” Pavle asked anxiously as the two soldiers thrusted people onto the truck, trying to crowd them in even closer to make more space for the others. The moustached policeman also looked quite frightened, although he was yelling and thrusting people too. Finally, one of the two German soldiers jumped off the truck and closed the tailgate. He pounded his palm hard against the tin and waved to the driver. Off they went.

They passed by the Fire Department at Tašmajdan Park and then crossed Slavia Square, riding towards Karadjordje’s Park via the road to the Autokomanda, the former command centre of the motorized forces of Yugoslavia. Night had already fallen, the evening curfew had already started, so the streets looked empty and dark as if there was nothing else in the world except for that truck, grumbling and roaring through the empty city. As the truck bounced and shook, the bodies on the truck staggered and collided with each other. With the noise of the engine in their ears and the wind in their eyes, they grabbed each other looking for support. Only fear and suspense drummed louder in their ears than the engine of the truck, echoing with every kilometre passed.

“Pavle, my son,” father touched Pavle’s ear with his lips, “See to it that you don’t arrive with us where we are being taken to.”

Pavle was silently staring at one point, somewhere above the father’s shoulder. His thoughts were swarming rapidly in his head, his forehead frowned more and more, while the shadows and lights of the street lamps alternated rhythmically over his face. Then he abruptly ran his fingers through his hair and remained in that position as if he was holding onto the single lock that was admired so much by Aleksandar.

“Uncle…” Pavle uttered dryly, fighting with the wind, fear and a hard decision he had to make very fast. Father looked deeply into his eyes, smiled tenderly, taking him secretly by the hand in the crowd of the squeezed bodies.

“Don’t worry about us!” said father and squeezed his hand harder. Pavle looked at him silently for a while and then responded by squeezing his uncle’s hand.

At the very next curve, when the truck slowed down a bit, Pavle suddenly pushed the first man next to him onto the German soldier grasping the edge of the truck’s railing and then jumped. As Pavle was flying over the railing, it seemed that everything stopped and froze for a moment. Time stopped too. No one was breathing, and the truck engine seemed to be mumbling from somewhere deep under the water, muffled and dull. Only one voice, Aleksandar’s father’s voice, echoed sharply and loudly through the night.

“Run, my son, run Pavle, dear boy!”

“Halt, halt!” the German soldier bellowed as he was getting up from the truck floor, taking his gun off his shoulder. Then the truck abruptly braked with the squeaking and rattle of tin and metal, once more making everyone stagger and fall down. The sound of the truck’s cabin door opening and the officer yelling something in German were heard. Then two shots from a handgun, followed by one more shot from the gun of the German soldier on the truck. After the shots, everyone was silent and listening, both Germans and Jews, as well as the moustached Serbian policeman.

For a few long seconds the silence lasted and then everyone could clearly hear branches cracking under Pavle’s young legs, running as fast as the wind would carry him, deeper and further into the safety of the dark.

“He made it! He ran away!” someone uttered excitedly, as if every single one of them had escaped.

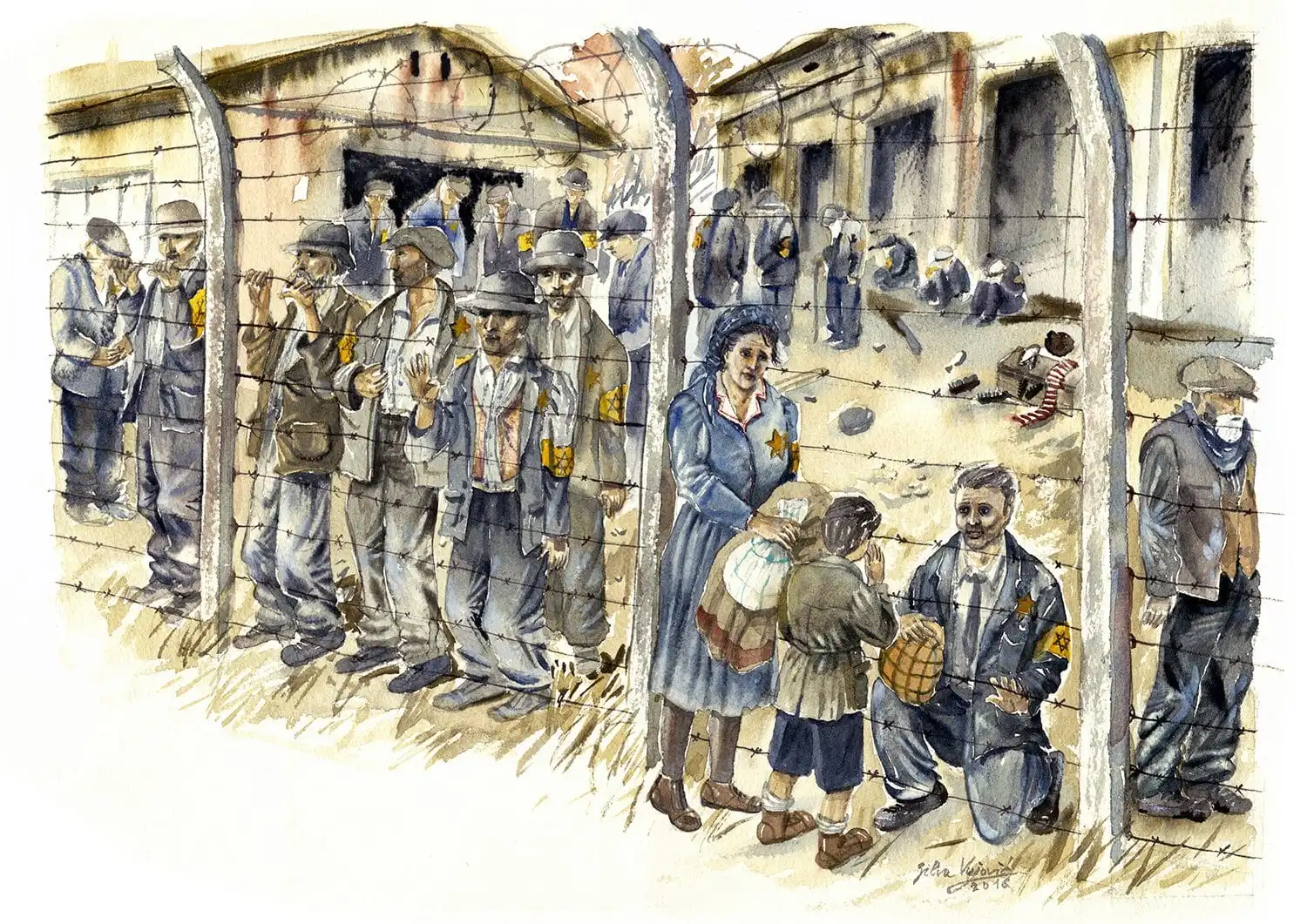

The Synagogue during Occupation

Aleksandar and Selma had practically not left their flat for several months. Mother would say that it was too dangerous for Jewish kids to be in the city even with their parents, let alone unaccompanied. On the other hand, almost every day mother would go visit father at Topovske Šupe concentration camp on Autokomanda to bring him some food. Aleksandar and Selma would stay at home alone, or their aunt would come to spend several hours with them. Since the day uncle Julije had not returned from his forced labour shift, there had been no trace of him. Father did not find him among the other inmates of Topovske Šupe. Nobody knew what had happened to him. They suspected the worst. Nor did they have any news about Pavle. Aleksandar heard them mentioning that Pavle “had run away to the woods”, but he couldn’t understand what exactly that meant. No one wanted to explain it to him but he did understand that in some way Pavle had somehow outwitted the Germans, which made Aleksandar happy. His aunt was beside herself with worry. Mother would ask her to stay overnight with them in the flat but she kept refusing, hurriedly returning back to her home before the evening curfew so that she could “be there for Pavle and Julije if they came back”. Since the evening curfew for Jews would start even earlier than for the rest of the citizens, the aunt was always in a hurry.

“Well, at least you must eat with us!” Mother would say but the aunt would just wave it off saying that it was the children who had to eat, for she already had lunch before she left home.

Aleksandar didn’t believe that his aunt already had lunch because she looked so thin and pale. Besides, earlier he had heard his mother complaining that it was very difficult to get food on the black market because everything was so expensive and Jews were forbidden to buy goods before half past 10am. After that time there was nothing to be bought in the already poorly stocked shops. Prices at the green markets kept rising because of shortages and counters were half-empty. Nor was there any money because father had not received his salary since April, when he had been thrown out of work since Jews were forbidden to work in public services. That was why mother sold grandmother’s jewellery and later on, even the dining table made of oak wood. Selling the table made the father angry but mother would respond that “they had to live off of something”. Now, they sat around an old small table that was covered with a dry cracked veneer instead of the oak dining table. That small table used to stand on the mezzanine floor of the stairway landing and they used to put flowerpots on it. On the other hand, Aleksandar’s aunt had nothing to sell because they had been thrown out of their apartment in the synagogue way before their own misery. That was why mother would say, “We all have to help and take care of each other, at least us, the closest ones.”

After the aunt would leave them, mother would sit in the kitchen crying, with her hands covering her face. She worried about father and all of them. Selma would come to mother and caress her knee. Aleksandar would go to his room and get under his bed to play with his red race car. It was then that he would think about his classmate Bogdan, whom he had not seen for a long time because Germans forbade Jewish children to go to school.

Nor was father there anymore because he was imprisoned in Topovske Šupe. There is a lot that is not there anymore, Aleksandar thought, rolling his red race car left and right under the bed.

But that day it was the Jewish New Year – Rosh Hashanah. They used to go to the synagogue to visit uncle Julije, the aunt and Pavle during Rosh Hashanah every year. Having given it a good think, the mother decided that in spite of everything they should go and visit their aunt, “to be there for her now that she was having the hardest of times.”

Aleksandar patiently let mother comb his hair. Today, he wanted to do everything to please her and to help, so he didn’t protest about mother’s insisting that he be “tidy and neat.” When Aleksandar and Selma were ready, mother first looked at herself in the big mirror that was in front of the door, combing her hair and adjusting the blouse around her neck and over her shoulders. Then she took two linen yellow stars from the top shelf and attached them to the back and front of her hanging raincoat with safety pins. After that, she put on her raincoat and silently tightened the yellow armband around her sleeve. There was a star of David on the armband, above and below the star “Jevrejin” in Serbian and “Jude” in German was written. As she opened the door, she avoided looking into the mirror again. She took a little basket and silently beckoned the kids to come along with her.

They walked down Dobračina Street and then went along Laze Pačua Street towards Knez Mihailova Street, sticking to the narrow alleys and shortcuts all the way to Obilić Crescent. It was as if the whole city loomed over them and they became tiny figures in a maze. Mother walked with hasty steps pushing the children before her. She walked upright, with her head high, looking straight in front of her, avoiding the looks of passers-by.

At Obilić Crescent, mother told the children to wait and then approached a group of men who were standing aside on the pavement holding some shopping bags in their hands. They had a short conversation. Mother took out something from her wallet. One of the men took it and quickly put it in his pocket, while the other pushed something wrapped in newspapers into her little basket. She came back to the children and explained in short, “I bought two apples and some honey from the black market, so that your aunt and us can treat ourselves for the holiday.”

They descended the stairs and arrived at Kosančić crescent, just in front of the synagogue.

In the synagogue’s courtyard there was a group of drunken German soldiers grimacing arrogantly, roaring and laughing, standing beside some women with red or bright orange messy hair. Some of the Germans were holding bottles and taking long gulps, thrusting the bottles into the womens’ hands from time to time to make them drink. Or, they would pour liquid over their heads and breasts. Music could be heard coming from a radio somewhere-– a deep female voice sung in German. All over the courtyard there were scattered wooden pews taken out from the synagogue. A couple of officers sat on them smoking cigarettes. All over the paved stone ground, colourful splinters of broken stained glass were spewn, which used to decorate the windows of the synagogue. Empty bottles and other scrap glittered. The gate and fence was broken down. The synagogue itself looked miserable, as if beaten up. The star of David on the top of the building was taken down. Instead of stained glass, there were planks and sheets of cardboard nailed over the windows with some thick curtains fluttering here and there. One German in his undershirt yawned loudly, stretching at the top of the stairs in front of the entrance to the synagogue.

It was such a terrifying scene that Aleksandar, Selma and their mother were completely speechless from horror. Selma might have even cried but at that very moment the German in the undershirt spotted them and started yelling.

“Sau Juden! Ihr dreckigen Juden!”

Frozen by fear, all three of them looked straight in front of them and stiffly walked fast, at an almost running pace before turning around the corner. Just some ten meters away there was a shanty that the aunt now lived in. Totally pale, mother knocked on the door loudly. She never stopped knocking until the aunt peeked out and opened the door wide.

“What are you doing here? My darling children, my dear Ranka, what are you doing here?” She was surprised for an instant and then quickly pulled them inside, “come in quickly, this street is full of Germans.”

They were all silent for a while.

“Shanah Tovah!” mother said, handing the aunt the little basket.

Parting with the Father

On the day before Yom Kippur, one of the Jewish high holidays and a day of repentance, mother told Aleksandar to get ready because he was going to visit father at Topovske Šupe concentration camp. Father requested to see him.

“Ner akhayim-for the life, Ner neshamah- for the soul.” mother said aloud as she lit two candles on the table.

“Mother, the candles are so small!” Selma said surprised.

“There are no candles, Selma, we have to save them,” mother responded.

Their aunt stayed with Selma, while Aleksandar and mother packed a piece of bread and an onion in a piece of checkered cloth for father as they left the flat.

They walked because Jews were forbidden to ride the tram. They walked for quite a long time. Mother was wearing a yellow star on her coat and a yellow armband. She was silent as she hurried forward with such long steps that time and time again, Aleksandar had to run to catch up with her. Finally they reached the concentration camp Topovske Šupe. Several brick buildings that used to serve as cannon and gun storage by the Yugoslav Army before the war, as well as the surrounding area, were turned into a camp for Jewish and Roma men by Germans.

German guards were at the main gate. Mother said that they had to go around to find father behind the fence at the other side of the camp. As they approached, Aleksandar saw many people behind the wire. They were all tired, ragged and dirty, wearing yellow stars on their chests and yellow armbands. A violin was heard somewhere from the camp accompanied by a hoarse voice singing in the Roma language. When they were just steps away from the wire, it seemed to Aleksandar that all the camp’s inmates were looking exactly at him with their watery eyes and pale stares. He snuggled up to his mother and took her by the hand.

Then he saw his father. Father was standing behind the wire, leaning against the concrete post which held the fence together. He was all bent, feeble, dusty and grey in his face, with big bags under his eyes and sunken eyes. Aleksandar was appalled by the sight and to him, the wire fence seemed to have extended and reached halfway up the sky.

– Riharde, pa ti goriš u groznici! – zajecala je majka. “Have you lit the candles? Erev Yom Kippur , you haven’t forgotten?”

asked father, as if checking if he himself hadn’t forgotten, without waiting for the answer. “I have lit the candles. Don’t worry!” mother kept repeating. He bent down on his knee, clasping the wire convulsively with one hand and crumpling his cap with the other, as if he could squeeze water out of it to quench his unbearable thirst. He solemnly looked straight into Aleksandar’s eyes. Aleksandar was breathing short and fast. His father’s eyes were shimmering with a glow, while his lips moved from time to time as if he was saying something mutely. Then his father stretched out his arm slowly through the fence and handed his cap to Aleksandar.

“Take it, my son. Take it, Aleksandar. I won’t be needing it any more.”

“But, father…” stammered Aleksandar.

“What are you saying?” mother stared blankly.

“Aleksandar, my son, do you remember the story about Jonah?” father continued, stressing every single word with a calm voice. “You do remember, I know. We always tell it on Yom Kippur. Far away on the high seas Jonah’s ship was caught in a strong storm. And Jonah was swallowed by a big fish. He lived three days and three nights in the belly of the big fish and after three days, God took pity on him and Jonah survived,” then father took a short break, looking into Aleksandar’s eyes to make sure that his son understood him.

“And just as Jonah lived in the belly of the big fish for three days in the terrible darkness and survived, so shall you, survive this darkness, my son. You must survive, you must promise me that!”

Aleksandar slowly stretched out his arm, and as if being enchanted, put his hand down on his father’s cap. He felt the cap soaked with his father’s sweat. His father’s index finger convulsively caressed his fingertips for a little moment. Then his father quickly pulled his arm back behind the fence. Standing on the other side of the wire with his father’s cap in his hand, Aleksandar raised his eyes and saw tears running down his father’s cheeks.

“You’d better go to avoid the evening curfew” father coughed and got up on his feet, wiping the tears off his face quickly, “Thank you for the food. Kiss Selma for me”.

***

Father stood leaning against the concrete post which held the fence around Topovske Šupe concentration camp. He could feel his fever rising and his body’s strength leaving him. The high pitched sound of the Roma violin played faster and faster behind him in the barracks. Through the metal fence as if through a spider’s web, he watched his wife and Aleksandar walk away. They did not turn around. Aleksandar was holding his cap in his hand.

Words and thoughts swarmed in a whirl, catching up with each other, not letting him think straight. Father mused. The Germans turned Belgrade into Nineveh, the city of sin and godlessness. God should have sent Jonah again to redeem the Ninevites of their coming destruction. God shall forgive our Belgrade one day too, just as he took pity on the Ninevites. Tonight, on the eve of Yom Kippur, His mercy will be back, it will be so. God will take pity. Aleksandar’s father got on his knees. I only pray the Lord forgive me that I shall not be there to take care of my son and watch him grow up. Forgive me for the vow I made, dear Lord for I shall not be able to keep it. I shall not be able, my son, Lo Alehem. You forgive me too, forgive your father! Barukh Shem kevod malkhuto le-olam va-ed! Barukh Shem kevod malkhuto le-olam va-ed! Father beckoned. You are no longer a child, my son. We have no time left for you to be a child! You haven’t had your Bar Mitzvah but this came along instead of your Bar Mitzvah. This was your Bar Mitzvah, today.

“Do you have some food?” a fellow camp inmate uttered in a tired voice.

“Yes, I do, Mošo, here you are. Share it.” Father handed over the parcel wrapped in checkered cloth to Mošo.

Aleksandar and mother were only a few steps away from becoming out of father’s sight. He saw Aleksandar put on his cap and disappear behind the corner.

The father quietly started to sing Kol Nidrei.

Departure to the concentration camp at Sajmiste

There was a drawer in the kitchen cupboard where they kept many various keys. Aleksandar was always intrigued by that drawer because no one was quite sure what all the keys were for. They piled up during a lifetime, father used to say but Aleksandar couldn’t understand where all the keys had piled up from in the first place. Obviously, somewhere there were matching locks. From time to time he would open the drawer and look at the keys: long and short ones, curved and fine ones, heavy ones with thick bows. Maybe some were for high metal gates or big double doors decorated by carvings; or narrow and small ones for some cellar padlocks or for boxes made of rosewood decorated with nacre, where some grannies would keep their jewellery and old letters. Since Jews had been forbidden to go to school, Aleksandar spent most of his time reading books, playing with his red race car or looking at the keys in the kitchen drawer–imagining what kind of mysterious and magic locks they would open.

The day before, the police informed the Jews that “on the 8th of December all Jews registered in Belgrade must report to the Police Department for Jewish Affairs on George Washington Street 21”.

The order also proclaimed: “Every Jew is allowed to take only as much luggage as one can carry by oneself. When coming to sign up, everyone must hand over their apartment keys with their name and street address on a piece of paper attached to it. After leaving the flat, the door must be properly locked. Everyone should take a blanket, cutlery and enough food for one day. Whoever fails to come shall be severely punished.”

All Jews were being sent to a concentration camp.

The aunt arrived early that morning. She brought along a linen suitcase and a jar of plum jam. Mother said that she wouldn’t even dream of asking where she got the jam and how much she had paid for it. Following their mother’s directions, Aleksandar and Selma prepared some warm clothes, especially woollen socks, for “cold feet make you freeze faster” as she used to say. Mother anxiously walked up and down the flat, checking if everything was left clean and neat. Then she started to go through all the keys in Aleksandar’s favourite drawer.

“Dear Lord, what are we going to do with all these keys?” she asked aloud.

“Why, mother?” asked Aleksandar, “What is one supposed to do with keys?”

“Everything we are supposed to hand over to the Germans must be neat and the keys must be marked!”

“But, dear” interjected the aunt, “Only the apartment keys must be handed over!”

“I know, but what if someone comes and sees this mess and has no idea what all these keys are for?” mother kept insisting.

Then she closed the drawer and took out a piece of paper and a pencil.

“Dobračina…Dobračina…” mother kept repeating, “Dear Lord, what is the street number of our house?” she finally exclaimed.

“Еighteen, mother.” said Aleksandar.

“Eighteen.” mother repeated and wrote it on the paper.

“The Fre-lihs, Frelihs” repeated mother, “Can it be seen well? Is it legible? Oh my God, I wrote it so ugly.”

“But it is all right.” the aunt reassured her.

“And what about the keys in the drawer?” asked mother.

“Just write ‘various keys ’on a slip and leave it in the drawer with the keys.” the aunt suggested.

“That is exactly what I am going to do!” mother said and wrote, ‘various keys’. Then she rose to take a look at the words written from above like a painter, checking the proportions of his portrait. She bent down again to add ‘piled up during a lifetime’.

“There, they will understand that.” she said and put the slip into the drawer.

After that she went to the front door, took out the key from the lock, put it down on the kitchen table and attached a paper with their name and address to the key with a piece of string. She stood there for a long moment holding the key between her thumb and index finger, high above the table, watching over the words ‘The Frelihs, Dobračina Street 18’. She started shaking, bouncing and trembling while hanging onto the string. When the paper finally settled, mother sighed.

“That’s it… we are ready.”

When they came out onto the street, the air smelled of košava, a mix of wind and chimney soot. It was very cold. December could be so cold in Belgrade. Uncle Julije once said that the košava wind blows all the way from Ukraine smelling of shtetls, but Aleksandar didn’t know how the shtetls smelled and couldn’t recognize their smell in the wind. They turned right and walked to the corner of Dobračina and Gospodar-Jevremova Street, then through Gospodar-Jevremova Street to Francuska Street, walking further towards George Washington Street. Mother, aunt and Selma wore thick scarves wrapped around their heads, while Aleksandar had his father’s cap to keep him warm. Selma held her teddy bear Pepi in her hand while Aleksandar jammed his red race car into the pocket of his coat. After a few steps, he realized that the car was turned upside down. He turned it around so that the front of the car was sticking out of his pocket. Aleksandar wanted his red race car to see where they were going.

Both his mother and aunt carried a suitcase. They were heavy and it was not easy to carry them in the cold wind. However, to Aleksandar it seemed that his mother and aunt slumped more under the burden of the yellow stars sewn on their backs and fronts than under the weight of the suitcases, while the yellow armbands drained the strength from their arms and made the suitcases even heavier.

While walking down the street, they encountered more and more groups with suitcases and yellow stars, mostly women and children. Gradually they formed a procession of people walking silently. The fact that they were in a larger group didn’t make it any easier for Aleksandar. Instead they seemed even more helpless and lonely in that featureless procession of yellow stars. Aleksandar looked at the houses they passed by but there was nobody standing at the windows. A passer-by would come along and would hastily turn around the first readily available corner, as if hurrying to move as soon and as far away as possible from the procession that was becoming bigger, wider and longer with every step. Aleksandar shuddered wondering what it would be like in the concentration camp. Was it going to be like in Topovske Šupe? He could still see his father: grey, in tears with sunken eyes.

A large crowd of people gathered in front of the offices of the Judenreferat, Police Department for Jewish Affairs on George Washington Street 21. It looked as if the whole world was on the move! The only time Aleksandar recalled seeing so many people was at the races. However, he realized he had never seen so many Jews gathered in one place. German soldiers gave orders in front of the entrance, dividing the crowd into rows and calling small groups to move forward from time to time. On the other hand, those who had already finished at the police offices were being directed to the other side of the street, where German guards escorted them onto trucks headed for the concentration camp. Even onto carriages drawn by horses or oxen, or directed to walk on foot. People were pushing their way through the crowd, shoving and calling each other. “Koen, Koen! Altaras, is there anyone from the Altaras family? Kalderon, where are you the Kalderons?” Some were shouting trying to find their relatives so that they could stick together as they went on. And some of them were not Jews, as it was obvious because they didn’t wear yellow stars but came to say goodbye to their Jewish friends and relatives.

Thus, Aunt Zora ran into the Frelihs calling “The Hercogs, the Hercogs.“ Aunt Zora was related to them somehow but Aleksandar was not quite sure in what way. Once before, when they met her in the street, Aleksandar asked mother why Aunt Zora was not wearing a yellow star and she explаined that Aunt Zora’s father was a Jew but her mother was a Serb and that the Germans did not consider one a Jew if one’s parent was married to a Serb. All that had been quite confusing for Aleksandar and hard to understand, for he remembered clearly seeing Aunt Zora at the synagogue too. It was obvious that there was someone, probably some German clerk, who was somehow deciding who was and who was not a Jew by his illogical and arbitrary judgement. But Aleksandar remembered one more thing about Aunt Zora, she lived in the same apartment block as Bogdan!

“Have you seen my father’s family?” asked Aunt Zora breathless.

“No, we haven’t Zora but I’m sure they are here somewhere.” answered mother.

“Aunt Zora, Aunt Zora!” Aleksandar pulled her sleeve, “Do you know my classmate Bogdan Živković? Your neighbours the Živković’s? Will you inform them please, that we are being sent to a concentration camp!”

“I will, my darling!” Aunt Zora answered, she bent down quickly and kissed Aleksandar’s forehead loudly and then Selma’s cheek, disappearing into the crowd shouting “The Hercogs, the Hercogs.”

***

A few hours later, mother, aunt, Selma and Aleksandar approached the demolished King Aleksandar bridge with the procession of Jews. A new pontoon bridge had been constructed along the demolished bridge’s pier.

“We are being led to Sajmiste, the fairgrounds!” someone in the procession exclaimed, “It is a concentration camp for Jews now.”

Aleksandar wondered how the fair could be a concentration camp because his father had said that “It was the gate to Europe for our Belgrade.” But nothing could surprise him anymore, for uncle Julije had said that “War is a terrible evil that brings out an animal in a man.” That was why, he guessed, all these German soldiers who were escorting the procession became more and more nervous and rough as the day went on.

It was already late afternoon. The weather had been grey with occasional rain all day and now the rain turned into snow, squeaking under their feet. The snow was trodden, turning into pools and mud. All around him, Aleksandar felt the smell of coats taken out of wardrobes full of mothballs and lavender. People were breathing loudly because of fatigue and their breath turned into vapour that rose above the whole procession, winding up to the grey December sky. The sky was already murky in the dense fog and semi darkness. Ravens croaked, circling above the Sava river and around the demolished bridge piers.

“Aleksandar! Aleksandar!” a voice was heard. Aleksandar raised his head. For a moment he couldn’t see anything because his view was blocked by fluttering coats and scarves, sleeves, boots and suitcases. And then he saw Bogdan, standing aside just a few meters away.

“Bogdan!” exclaimed Aleksandar as he broke free from the river of people and ran towards his friend. They grabbed each other by the hands and looked at each other silently for an instant. Their hearts were pounding as if they would explode.

“You’ve come!” Aleksandar said proudly with a big smile all over his face. A German soldier started shouting at the boys furiously. Mother screamed from the procession “Aleksandar!”

“Don’t forget me!” said Aleksandar, breaking his hands loose from Bogdan’s and running back to the procession following his mother’s voice.

Aleksandar turned around a few more times, bouncing to see better. Bogdan was still standing in the same spot motionless. And then, pushed away by the steady and silent steps of people walking across the pontoon bridge, Aleksandar could no longer see him.

***

The knocking at the door broke the silence. Bogdan’s father opened the door and saw their neighbour Zora standing at the doorway. She dropped by to inform them that the Frelihs were sent together with other Jews to a concentration camp and that in that moment they were in the procession moving towards the fairgrounds. Bogdan didn’t hesitate a moment but jumped to his feet and started to put on his coat.

“Where do you think you’re going?” said his father with a serious voice.

“Father, I have to say goodbye to Aleksandar!” Bogdan stopped putting his arm halfway down his sleeve, “Please!”

His father was about to say something but Bogdan’s look confused him for a moment, for it was not a small boy standing before him but a grown up man, which suddenly reminded him of another occasion when he was a soldier of the Serbian army in the Great War. He couldn’t have left his wounded war comrade. He remembered how he had learned that there were only a few really important moments in life, a few crucial choices one could make, which would determine for the rest of our lives whether we were humans. Whether we had human dignity, a sense of right and wrong, conscience and moral duties-– or not. If that is one of these moments for you, then I understand, you have to go, thought Bogdan’s father. He sighed deeply and said “All right, son. Just be careful, please!”

Bogdan ran, losing his breath, stumbling down and getting up on his feet again, taking short-cuts and jumping over the fences. He and Aleksandar certainly knew this neighbourhood like the back of their palms. He got to the piers of the demolished bridge looking over the Sava river when the endless grey procession of people glided over the snow, heading to the pontoon bridge on their way to the other side of the river. Only the yellow stars and armbands shone as if the night sky was full of stars. He stood watching the procession hastily, bouncing to see those who were walking further away from him better. Then he saw Mr. Frelih’s cap, he was very familiar with it but this time it was on Aleksandar’s head.

“Aleksandar! Aleksandar!” he shouted with all his strength.

“Bogdan!” he heard Aleksandar’s voice as Aleksandar pushed through the procession and ran to him. As he approached, Bogdan grabbed his hands tightly. He wanted to tell him all sorts of things but he couldn’t find words.

“You have come.” Aleksandar said with his eyes full of happiness.

Then a German soldier started shouting at them.

“Don’t forget me!” Aleksandar let loose and ran back to the procession.

Bogdan followed Aleksandar’s cap for a while and then somewhere in the middle of the pontoon bridge he couldn’t see it anymore. He stood there, he didn’t know for how long. Only muddy footprints in the snow witnessed that there had passed a stream of people and that all of this was not a dream. He looked across the river not being able to move, an immense and terrible silence weighed down on his shoulders. It was only then that he noticed that during those few moments they had held each other’s hands and that Aleksandar pushed his red race car into his palm.

The Gas Van

The dense darkness filled the damp, dank air of the former fairgrounds pavilion in Judenlager Semlin at Sajmište. Aleksandar was very tired but instead of sleeping he listened to the inmates coughing every night, as if a sick orchestra had been playing a very complicated symphony. The coughs were accompanied by the monotonous clatter of the rain on the roof and the echoes of drops falling off the punctured ceiling and splashing into puddles all over the pavilion. He had not been able to warm himself up since the košava wind crept into his frail child’s bones during that winter. It seemed to him that somewhere on his back there were four or five icicles hanging from his shoulders and shoulder blades that stabbed his lungs with their sharp points. I suppose that is why I also cough in the orchestra at night. Thought Aleksandar. He pulled his father’s cap down tighter over his ears and face trying to feel the smell of father’s hair and perhaps fall asleep hidden in it.

Aleksandar had been taking care of Selma, mother and aunt. After all, he had promised his father that he would take care of all of them since he was the only man in the family now.

Mother used to say that hunger filled the pavilions with anxiety and anger, while reason melted like а thin candle in the wind. Selma was so weak and meagre that mother kept fearing that she might simply succumb to exhaustion and die before her eyes any minute! The aunt was approaching that state too. “Poor thing, she is barely of sound mind” mother used to say. Aunt would sometimes speak with uncle Julije and Pavle as if they were there and mother would hug her, pressing her to her breasts and repeating “Just a little bit more, hold on just a little bit more, b’ezrat Hashem!”

Aleksandar also kept repeating to himself, just a little more, hold on one more day. He firmly believed that their turn would come to be transferred to that other camp, a labour camp in Romania or Poland-–he was not quite sure where to-–as long as they would leave that horror and stench. Never before had Aleksandar seen dead people, but here in the camp he kept seeing them every day. Bodies lined up in the bathroom of the Turkish pavilion, the dead people were carried away from the hospital in Spasić’s pavilion to be taken across the frozen river Sava and buried at the Jewish cemetery. Some were shot by Germans in front of everyone between pavilions three and four. However, when Germans told them that the camp would be emptied and all inmates transferred, a new hope arose and that was why Aleksandar kept repeating affirmations to himself. They drove people away to the new camp day by day, their turn would come. He had been watching from afar, everyday groups of inmates got into the grey bus without windows. As a matter of fact, it looked more like a van. Then they would slowly set off towards the pontoon bridge over the Sava river, followed by another waddling truck that was loaded with the inmates’ stuff. Aleksandar wondered where they were being taken to and what that other place looked like. It was said that there were other Jews there who had already been transferred from other camps. Maybe father will be there waiting? Maybe uncle Julije got there even earlier? Only Pavle is not there. He’s in the woods. Aleksandar kept musing on.

He raised his head, took his father’s cap off his face and propped himself up on his elbows. His mother lay next to him, embracing Selma and from the other side, Selma was embraced by the aunt. Thus, they kept Selma warm with their own bodies. He couldn’t see them in the darkness but he could feel them, together with the rest of the several thousand inmates’ bodies squeezed together on the floor of the pavilions. Then he lay down again, pulling the cap over his face.

Aleksandar had been familiar with this space, though it looked quite different during the Car Exhibition. Back then, the chrome parts of brand new car models gleamed, their shining bodyworks reflecting the spotlights. He was amused by the thought that he might have lay on the very same spot where that new Mercedes Benz had been parked, which he looked at almost two years ago.

He put his palms over his face, pressing his father’s cap to his eyes, mouth and forehead as if he was washing his face.

All of a sudden, neon letters lit up on the walls of the pavilion: Steyr-Daimler-Puch, Buick, Saurer, Cadillac, Tivar, Hotel Moskva, Mercedes… Father was talking to Mr. Demajo, Aleksandar stretched his arm over the rope to feel the cold metal of the chassis of the car. Somewhere from behind, Pavle’s voice said that German cars were the best. Aleksandar turned around, yet Pavle was not behind him. Instead, a big blue bus moved slowly, gradually approaching closer and closer. Aleksandar kept rising up on his toes in order to see better through the front windshield but instead of a driver and passengers there was only water up to the roof of the bus. The water leaked in thin streams through the edges of the doors and windows splashing onto the puddles all over the pavilion. Fish flapped and gasped on the floor. “Aleksandar, Aleksandar” he heard Bogdan calling him. For a moment he couldn’t see anything because his view was blocked by fluttering coats and scarfs, sleeves, boots and suitcases passing by in the procession. And then he saw Bogdan standing aside just a few meters away, “Bogdan!” exclaimed Aleksandar breaking free from the river of people and running towards his mate. “Hurry up! Let’s go!” Bogdan shouted pointing at the shining red Mercedes Benz W-154 M163, the invincible race car of the world champions. Aleksandar was shifting gears convulsively squeezing the wheel. Bogdan was sitting next to him beside the driver’s seat. They both had leather racing caps, which covered their whole face leaving just a little space above the nose and around the eyes for car racing goggles. Aleksandar’s racing cap smelled of father’s hair. Aleksandar and Bogdan were racing around Kalemegdan Park, puncturing the shouts of the excited crowd, the noise of engines and squeaking of wheels. They passed the stands where father and Pavle watched. What a surprise it would be for father and Pavle to see the two of them!

***

That morning, the German officer who handed out candies to the inmates’ children walked into the camp. Aleksandar saw him on several occasions during the last few days. This time, Aleksandar went to him to get a candy for Selma. He took off his hat and stood before the German.

“Wie heißt Du, mein Junge? Komm, nimm Dir einen Bonbon!” he said to Aleksandar with a gentle voice, holding out a single piece of candy wrapped in shiny silver paper in his open palm. Aleksandar took it quickly, while the German smiled and patted him on his head, ruffling up his hair. As he walked back to the pavilion, Aleksandar thought that his lock might now be hanging a little over his forehead in the same way Pavle’s lock did. But there was no mirror to check it.

He soon saw mother calling to him excitedly “We are packing up! We are leaving! Today our group is leaving, thank God!” she shouted, “We are instructed to take only valuable things with us, the rest must be wrapped in a package with our name written on it and will be delivered to us separately. Though, we don’t have any valuable things anymore…” mother said, as if to herself.

Soon after, they stood at the camp exit. Belgrade was shining across the Sava river, beautiful and silent. Just like the days before, there were two vehicles parked in front of a group of about 80 inmates. One of the two was an ordinary truck, where the inmates loaded their luggage. The other one was a grey van that looked like a bus, except that it did not have any windows and it was waiting for the passengers. Aleksandar took a look at it. The brand of the van was Saurer. He remembered seeing a similar bus at the Car Exhibition but he had never seen such a model-–one without windows.

The German who used to give out candies appeared, opening the door of the grey vehicle wide. “Auf geht’s, steigt ein, wir fahren los!” he invited them to step in, using a gentle voice and wearing the same smile he had when giving out candies to the children.

The inmates went inside two by two and sat down on wooden benches. Mother got in first, carrying Selma in her arms followed by aunt and Aleksandar. They sat crowded against one another. A murmur filled the tin vehicle. When the door closed with a bang, the passengers realized that the same damp and dank air from the pavilions in Judenlager Semlin was still following them. Together with the darkness, a silence crept in accompanied by fear.

While they swung in complete darkness as the van gasped and bounced, Aleksandar pulled down his father’s cap over his face as tight as he could and took a deep breath, searching for a trace of his father’s smell. He thought for a moment and took his cap off of his face.