1. The Belgrade Fair

The Belgrade Fair was built in 1937 . At that time it was a symbol of a new, bright future, a place where Serbia (being a part of Kingdom of Yugoslavia then) was to become a part of the modern Europe.

With the construction of the fair, the city of Belgrade crossed the Sava River for the first time, materializing an ambitious urban planning project on its opposite bank and opening a new perspective for the city’s development. In its early years, the fair attracted numerous investors and manufacturers, thereby also creating new opportunities for economic growth. Alongside Yugoslav pavilions, a growing number of international pavilions were established, including Hungarian, Romanian, German, Italian, Czechoslovak, and Turkish ones. Some of these were leased to major companies, which built and operated their own dedicated pavilions. Thanks to its modern atmosphere and striking architecture, the Belgrade Fair quickly became a popular destination for the city’s residents, who visited it to see exhibitions showcasing the latest technological innovations of the time. Notably, the Dutch company Philips broadcast the first television program in the Balkans from its pavilion at the Belgrade Fair. During the Belgrade Fair Aeronautical Exhibition, the Czechoslovak company Škoda constructed what was then the tallest steel parachute training tower in Europe, standing 74 meters high. The fair also hosted classical music concerts and art exhibitions. For many citizens of Belgrade, it became a favorite leisure destination—offering not only products and innovations from across Europe, but also a rich selection of restaurants and shopping stands.

Crossing the river Sava, the city of Belgrade was about to become a true European metropolis.

But instead of being a road leading to the bright future, the Fairgrounds would soon become a place where people were going to face terrible suffering and death.

The Belgrade Fair embodied the vision of a new, brighter future, representing Serbia’s aspiration—within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia—to become part of modern Europe.

2. The Occupation of Serbia

Under strong pressure from Germany, the Yugoslav government signed the Tripartite Pact on 25 March 1941. However, only two days later, on 27 March, mass demonstrations erupted in Belgrade and other cities. Following a coup d’état, a new government was formed that refused to ratify the Pact and rejected an alliance with Nazi Germany.

In response, Adolf Hitler decided to launch a ruthless military campaign aimed at the destruction of Yugoslavia, both as a state and as a political entity. With the support of neighboring countries Hungary, Italy, and Bulgaria, and aided by internal collaborators, Germany attacked Yugoslavia without a declaration of war.

On 6 April 1941, the German air force bombed Belgrade with extreme brutality. The bombing continued on 7 and 12 April. During the air raids, more than 2,000 residents of Belgrade were killed, a large number of buildings were destroyed, and significant cultural heritage was damaged or lost. 11. After the brief April War, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was dismantled, and Serbia was occupied and partitioned into several occupation zones. The largest part of Serbia came under German occupation, including the Banat region, which was placed under the administration of the Volksdeutsche. Other parts of Serbia fell under the control of Hungary, Bulgaria, the Independent State of Croatia, and Italy.

Very soon, the Germans established a military occupation administration that included an extensive repressive apparatus, in which the Operational Group of the Security Police and Security Service (Einsatzgruppe der Sipo und des SD) played a central role. Its core was the notorious Department IV of the German Security Police—the Gestapo—within which the Police Department for Jewish Affairs (Judenreferat) was established immediately.

Viewing the destruction of the Jews as their primary objective, the Nazi authorities promptly began implementing a systematic plan to annihilate the Jewish population in Serbia under German control, with the active assistance of the Serbian quisling regime. Under threat of the harshest penalties, Jews were ordered to register and to wear yellow armbands for identification. Anti-Jewish measures were introduced step by step, accompanied by the widespread dissemination of antisemitic propaganda.

During the summer of 1941, resistance against the occupation spread throughout Serbia. In response, the German authorities attempted to suppress the uprising through extreme repression of the civilian population, including mass reprisal shootings. Civilians were arrested on a large scale and held as hostages, to be executed by firing squads in retaliation for attacks on German forces.

Jews, Roma, communists, and patriots who opposed the occupation and the quisling regime were particularly targeted as hostages, although many others were also seized. A German order stipulated that for every German soldier killed, 100 hostages were to be executed, and for every wounded soldier, 50.

Through these mass reprisal shootings, the German authorities sought not only to crush the uprising in Serbia but also to murder as many Jews as possible, as part of the broader plan to annihilate Europe’s Jewish population. During the autumn of 1941, arrests, round-ups, and mass executions took place across Serbian cities. Ordinary civilians—including peasants and even schoolchildren—were among the victims, as recorded in German reports stating that “not enough hostages could be found elsewhere.”

The camp at Topovske Šupe, located on the outskirts of Belgrade, was established in late August 1941. It held approximately 5,000 Jewish men—mostly from Belgrade and Jews expelled from the Banat region—as well as between 1,000 and 1,500 Roma men. The camp served as the primary “hostage reservoir” for German reprisal shootings.

Executions were carried out at sites such as Jajinci, Jabuka, and the Deliblato Sands. Within just a few months, nearly all Jewish men in the territory of Serbia under German control were murdered in mass reprisal shootings.

The implementation of mass reprisals served a dual purpose: the suppression of the uprising in Serbia and the systematic murder of Jews within the broader framework of the Nazi plan to distroy European Jewry.

3. The Concentration camp at Staro Sajmište

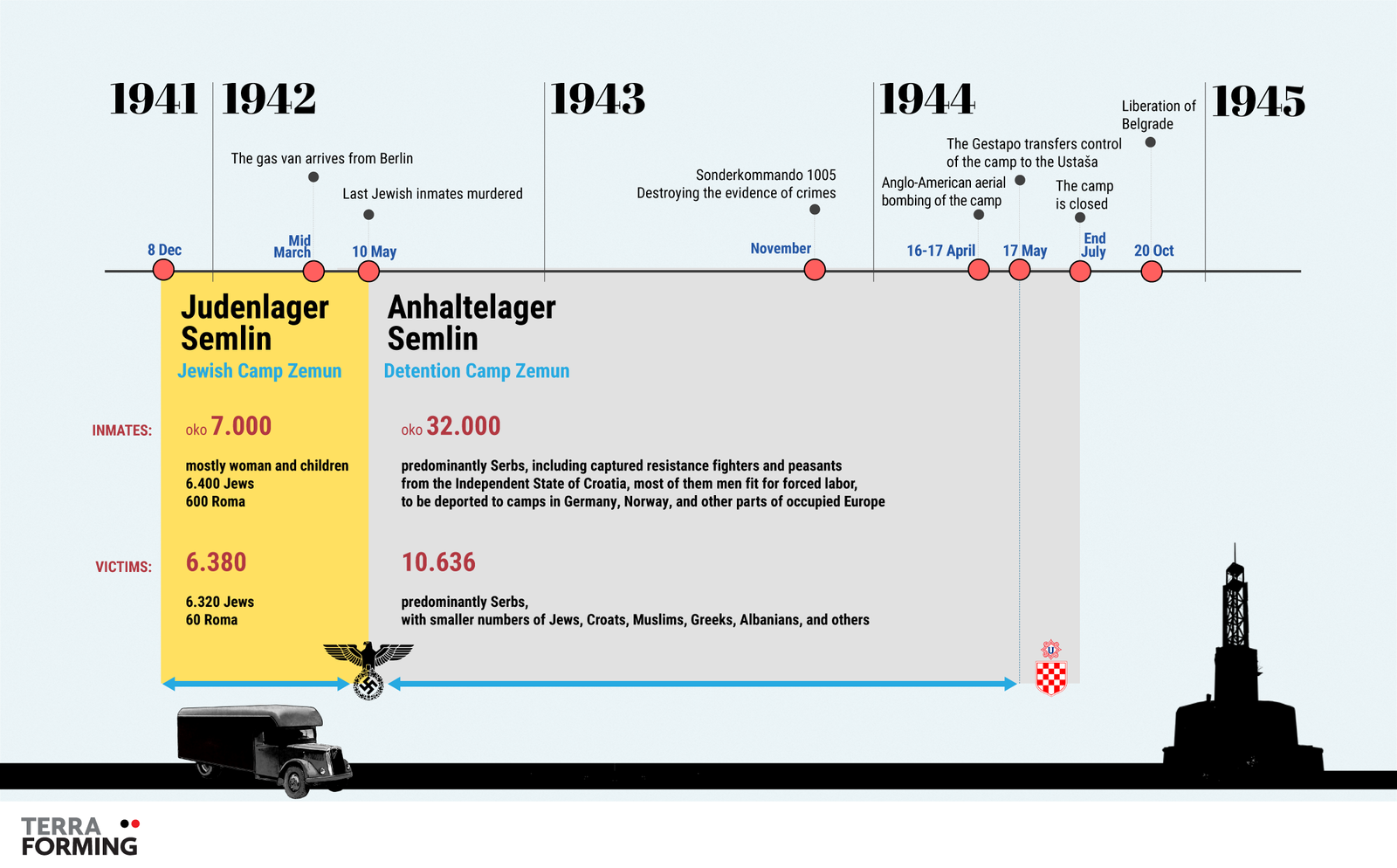

The Jewish Camp at Staro Sajmište (Judenlager Semlin)

Basic Information

- Purpose: destruction of the remaining Jews in the territory of Serbia under German control

- December 8, 1941 - the end of May 1942

- 7.000 inmates - 6.400 victims

Inmates: 6.400 Jews and 600 Roma.

Victims: 6.320 Jews and at least 60 Roma.

The death camp at Staro Sajmište emerged as a central symbol of the Holocaust and the persecution and murder of Jews in occupied Serbia.

When the Germans transformed the Belgrade Fairgrounds into the Jewish camp Judenlager Semlin, it became a detention and extermination site for Jewish women and children. Although located just outside Belgrade, the camp lay within territory annexed by the Independent State of Croatia. Nevertheless, it was under full German control: administered by the Gestapo, commanded by SS officers, guarded by German personnel, and integrated into the German military occupation administration of Serbia.

Of the approximately 6,400 Jewish inmates held in the camp, the majority—around 5,500—were from Belgrade. The remaining prisoners came from the Banat region and other areas of Serbia under German occupation.

Between April and May 1942, over the course of just a few weeks, Jewish women and children were systematically murdered using a gas van (Gaswagen), known locally as the dušegupka. The vehicle, a Saurer truck, had been specially modified by engineers in Berlin to function as a mobile gas chamber and was delivered to Belgrade by two SS officers.

Under false pretenses that they were being transferred to another camp with better living conditions—where they were allegedly to be reunited with their husbands and fathers, who in reality had already been murdered—groups of 80 to 100 prisoners, mostly women and children, were forced into the van. The vehicle then crossed the Sava River into Belgrade via a temporary pontoon bridge constructed near the destroyed King Aleksandar Bridge.

After crossing the bridge, the SS drivers redirected the exhaust fumes into the sealed cargo compartment, filling it with carbon monoxide. As the van was driven through central Belgrade toward the execution site at Jajinci, the victims inside suffocated. By the time the vehicle arrived, all those inside were dead. Their bodies were then unloaded into mass graves prepared in advance.

Through this method of deception and industrialized murder, the Nazis killed approximately 6,320 Jews—predominantly women and children—out of the 6,400 prisoners held in Judenlager Semlin.

SincSince most Jewish men had already been executed in mass shootings in the preceding months, the murder of the remaining Jewish women and children at the Sajmište camp led the Nazis to cynically conclude in their reports that “the Jewish question in Serbia had been solved.” Thus, the death camp at Staro Sajmište stands as a symbol of the Holocaust and Jewish suffering in occupied Serbia.

At the same time there were about 600 Roma inmates in the camp at Sajmište, out of which at least 60 died during the wintertime, mostly of hunger, cold and disease, while the rest were released later.

Carbon monoxide poisoning:

- nausea, headache, dizziness,

- disorientation in time and space,

- muscle weakness, disturbed vision,

- muscle cramps, seizures,

- coma, cardiorespiratory failure,

- loss of brain function,

- death

The Detention camp at Staro Sajmište

Basic Information

- Purpose: detention camp for the captured members of the resistance movement and Serbian men from the territories where military operations were conducted (largely from the Independent State of Croatia) and their deportation to forced labour and concentration camps

- the end of May 1942 - the end of July 1944

- 32.000 inmates - 10.636 victims

Inmates: 32.000 mostly Serbs, Serbian peasants from Independent State of Croatia and captured members of the resistance.

Victims: 10.636 mostly Serbs, and some groups of Jews, Croats, Bosnian Muslims, Greeks, Albanians and others.

The detention camp at Staro Sajmište was notorious for its harsh conditions and cruelty. Although it was not initially established as an extermination camp, it proved to be extremely deadly: approximately one third of those who passed through the camp died there.

After the extermination of the remaining Jews in the territory of Serbia under German occupation, the camp at Staro Sajmište was transformed into a detention camp, whose inmates were predominantly Serbs. The camp continued to be administered by the German authorities.

In this phase, the detention camp served the strategic purposes of suppressing the resistance movement and providing forced labor for Hitler’s war economy. Among the prisoners were large numbers of captured Yugoslav Partisans, as well as members of the royalist resistance movement. However, the largest group consisted of Serbian civilians fit for work, transferred from areas affected by military operations—primarily from the territory of the Independent State of Croatia.

Many of these prisoners were held at Staro Sajmište only temporarily before being deported to forced labor camps and concentration camps in Germany, Norway, and other German-occupied countries. At various times, the camp was also used for the temporary detention of Jews deported to death camps from territories occupied by Germany after Italy’s capitulation, as well as from other occupied regions. In addition, smaller groups of captured Greeks, Albanians, and others were imprisoned in the camp for shorter periods.

The detention camp at Staro Sajmište was notorious for its harsh conditions and cruelty. Although it was not primarily intended as a killing site, it proved to be extremely deadly: approximately one third of all those who passed through the camp perished there.

Prisoners were subjected to brutal treatment and held in appalling conditions. Many died from hunger, exhaustion, and disease, while others were killed as a result of constant abuse by camp guards. Beatings to death were common, and some inmates were shot or hanged.

After the camp was bombed by Allied Anglo-American air forces in April 1944, many inmates were killed as a direct result of the air raids, and the camp facilities were severely damaged. In May 1944, the Nazis transferred control of the camp to the Ustaša Police of the Independent State of Croatia, although it continued to be used primarily for German purposes.

As the number of prisoners declined and it became increasingly evident that the war was turning against Germany and its allies—while Yugoslav Partisans and the Red Army advanced—the camp was abandoned by the end of July 1944. The remaining inmates were transferred to other, smaller camps.

On the 20th of October 1944 Belgrade was liberated by the Yugoslav partizans, aided by the Red Army.

4. Victims at Staro Sajmište

Inmates

Killed

The Victims of the Camp at Staro Sajmište

From the first day of its existence, on 8 December 1941, until its abandonment at the end of July 1944, a total of 38,972 inmates were detained in the camp established at the Belgrade Fairgrounds. Of these, 17,016—approximately 43.7 percent—lost their lives.

Cover-Up of Crimes

Units of “Special Command 1005” (Sonderkommando 1005) arrived in Belgrade as early as November 1943. Their primary task was to eliminate all traces of the mass killings committed by the German authorities. As part of these hastily organized operations, prisoners were forced to exhume mass graves and burn the corpses in order to obstruct the identification of victims and to make it as difficult as possible to determine the true number of those murdered.

For four consecutive months, such operations were carried out at killing sites around Belgrade, Niš, Petrovgrad (today Zrenjanin), and other locations. Among the exhumed and burned bodies were those of Jewish victims who had been shot in mass executions, as well as those who had been suffocated in the gas van.

5. Memorial Center "Staro Sajmište"

No memorial centre or museum have been built on the former campgrounds for decades. For a long time the area where the camp was located was in a very poor condition as a result of disuse and neglect.

Unfortunately, as a result of neglect and lack of maintenance, the historical buildings and authentic places of suffering at Staro Sajmište and Topovske Šupe are still in very poor condition today, and their survival has long been threatened.

By participating and initiating international projects related to this history, creating educational materials and training programs such as Ester, through the #SaveSajmiste #SaveTopovskeSupe campaign on social networks, Terraforming, too, tried to contribute to raising awareness about this issue.

In May 2019, the Government of the Republic of Serbia formed a working group tasked with preparing a proposal for the Law on the Memorial Center “Staro Sajmište” . 24. In February 2020, the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia adopted the law. The law stipulates that the future institution, in addition to the Staro Sajmište site, will also take care of the Topovske Šupe camp location.

After intensive work on the renovation of the central tower, the Memorial Center “Staro Sajmište” has gained a beautiful space, and one of the authentic buildings has been saved from decay. There is now an exhibition space, and space for various activities and events. In addition, the Memorial Center also uses the premises of the neighboring building, a former school, which houses offices and a classroom.

I

In addition to the extensive and demanding task of preserving and renovating the remaining authentic buildings and spaces, we face a new—perhaps even greater—challenge: to create an institution that will contribute to the development of a culture of remembrance, advance modern education and research, and serve as a bulwark against the distortion, politicization, and manipulation of history.

This process began with the establishment of the new Memorial Center “Staro Sajmište”, which in the years to come will be tasked with addressing all of these challenges.

Moreover, bearing in mind the specific history of the Holocaust and wartime suffering in our region, as well as the global need for a deeper understanding of local Holocaust histories within a broader European context—particularly in Eastern and Southeastern Europe—we have a unique opportunity for the new Memorial Center Staro Sajmište to become one of the leading European training centers.

The Center has the potential to serve educators, librarians, archivists, doctoral students, as well as decision-makers, policymakers, young volunteers, and other stakeholders from across Europe, working in the field of Holocaust education and memorialization.

Terraforming will continue to support this process and contribute to its realization within its capabilities.

6. The "Remembering Hilda Dajč" Award

Who is Hilda Dajč?

Hilda Dajč was born in 1922 in Vienna, Austria, into a wealthy Ashkenazi Jewish family. Her parents were Emil and Augusta, and a younger brother, Hans. When Hilda was very young, they moved to Belgrade.

Before the war, after graduating from high school as one of the best students of her generation, Hilda enrolled in architecture studies at the University of Belgrade. With the invasion of Nazi Germany into Yugoslavia in April 1941, Hilda had to interrupt her studies. She soon volunteered to work as a nurse in the Jewish hospital in Belgrade.

Hilda’s father, Emil Dajč, took on the role of vice president of the Representative Body of the Jewish Community in Belgrade. In December 1941, after most of the male Jewish population in the country had been killed as part of the executions carried out by the Wehrmacht in response to the uprising in Serbia, Jewish women and children were taken to the newly established German camp for Jews, Judenlager Semlin, the camp at Staro Sajmište. Although the families of the leadership of the Jewish Representative Body were not required to comply with this order at the time, Hilda, despite her parents’ opposition, voluntarily signed up to go to the camp and work as a nurse in the camp hospital. Hilda’s family was also sent to the camp several weeks later.

Hilda wrote four letters from the camp to her friends. These letters are a rarely preserved testimony of life and suffering in the camp.

Sometime between April and May 1942, Hilda was killed along with all the other approximately 6,500 Jewish prisoners in a gas van – a mobile gas chamber.

On 10 May 1942, the last group of Jews held in the concentration camp at Staro Sajmište was murdered. Shortly thereafter, a report was sent to Berlin stating “Serbia ist judenfrei” (“Serbia is free of Jews”), using the cynical terminology of the Nazi authorities.

In 2014, the Assembly of the City of Belgrade decided that May 10 should be Remembrance Day for the Victims of the Holocaust in Belgrade.

"Remembering Hilda Dajč" Award

The “Remembering Hilda Dajč” Award is an annual recognition established in 2022, on the 80th anniversary of the murder of the last group of Jews in the camp at Staro Sajmište. The recognition has since been awarded every year on May 10, Remembrance Day for the Victims of the Holocaust in Belgrade.

The initiative was launched by non-governmental organizations Terraforming and Education for the 21st Century and a group of activists and enthusiasts.

The recognition is awarded in two categories: Youth Recognition for Civic Responsibility and Social Awareness, and Recognition for Outstanding Contribution to the Culture of Remembrance.

The Youth Recognition is awarded for demonstrated special personal and civic responsibility, social awareness, dedication, solidarity and humanity, identification of problems and initiation of action, especially in their local communities.

The Recognition for Outstanding Contribution to the Culture of Remembrance is intended for individuals, groups, organizations or institutions from the Republic of Serbia, or from other countries, who have made a significant contribution to nurturing, promoting and strengthening the culture of remembrance of the Holocaust in the Republic of Serbia.

Candidates are nominated by citizens through a public competition, nominations are approved by the Management Board, and awards are given by a jury consisting of last year’s winners and invited jury members.

You can read more about the recognition, previous winners and candidates for this year’s recognition on the website www.hildadajc.rs